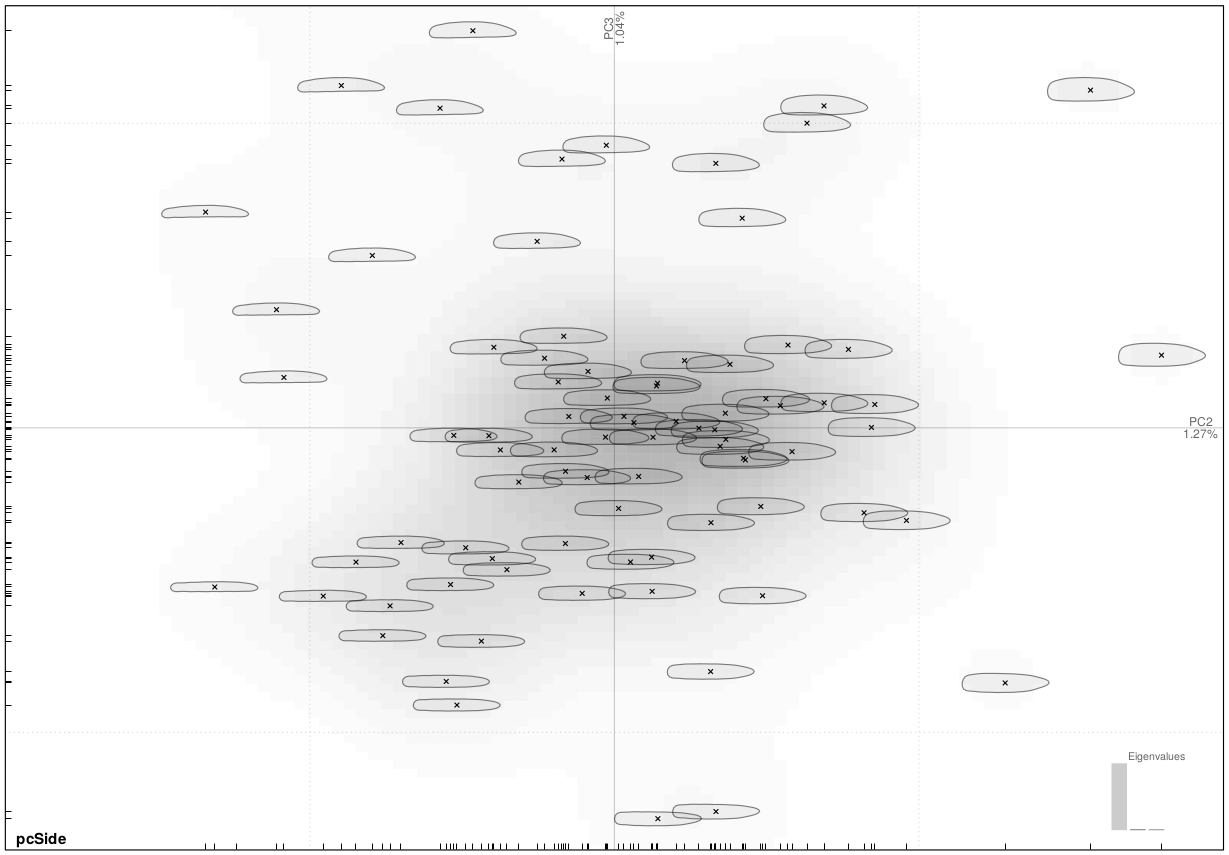

Variation in the shape of

polished and beveled stone tools

Result of small decisions within borders of shared manufacturing practice

Petr Pajdla 1,

petr.pajdla@protonmail.com

1 Department of Archaeology and Museology, Masaryk University, Brno

Introduction

There is some variation in the shape and size of polished stone tools (axes, adzes etc.) In archaeology, we use this variation to construct types, usually with ascribed chronological significance. Here we will explore the origin of this variation.

Figure 1: Variation in shape of LBK adzes, side view

Problem

The variance in shape can occur in (at least) two points in time:

- During the manufacturing process

- During the use and reparations of the tool

Changes in shape during the use are limited to resharpening of the working edge of the tool or reparations of the part that is attached to the shaft.

The changes in shape during the use phase of the tool are thus usually minor ones but stacked together, these might lead to larger differences.

In our point of view, the manufacturing process is nevertheless the main source of shape variation of the polished and beveled artefacts.

Manufacture

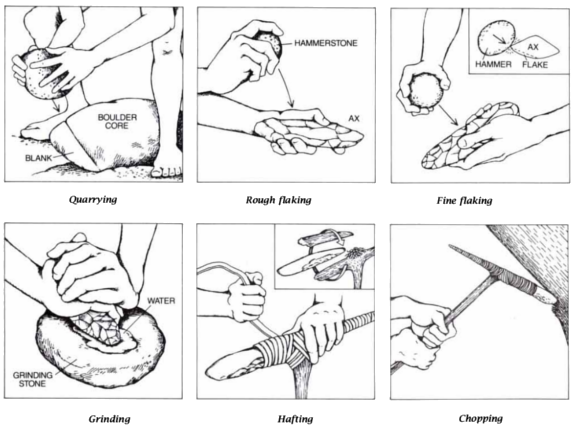

Figure 2: Idealized manufacture process (Toth 1992)

We have quite a good idea of the manufacturing process of polished and beveled stone tools thanks to analogies from New Guinea (e.g. Pétrequin – Pétrequin 2011; Hampton 1999; Toth 1992 etc.) and documented quarries (e.g. Prostředník – Šída et al. 2005; Pétrequin – Pétrequin 1998).

A complicated process?

- Quarrying a stone block

- Rough flaking into an amorphous roughout

- Fine flaking into a blank resembling the ideal final product in shape and size

- Grinding the working edges or the whole surface

- Fine polishing…

The process needs to be learned!

The case of LBK pottery

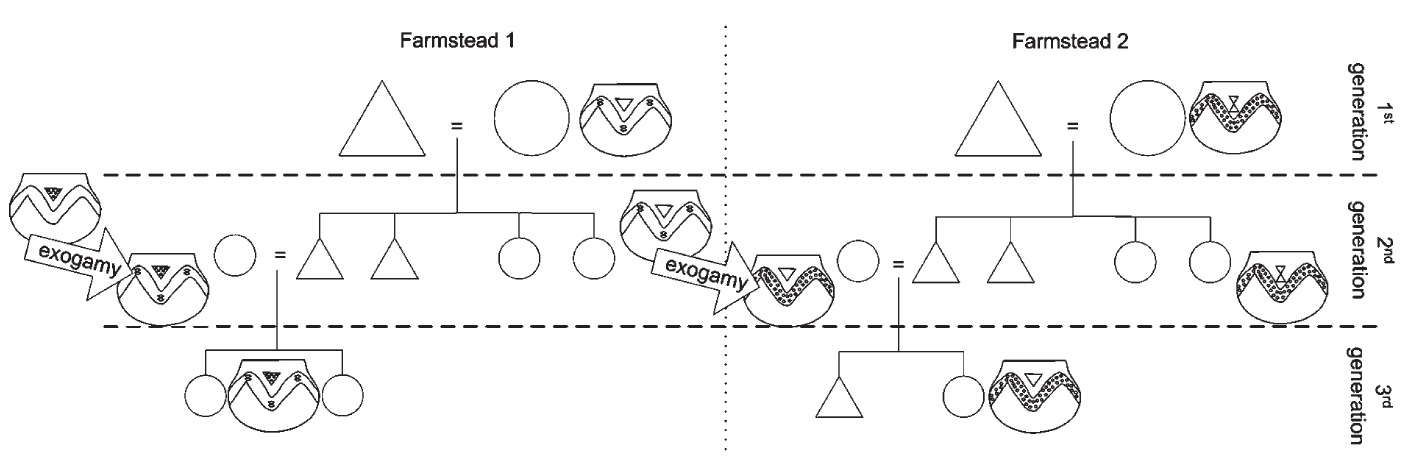

Figure 3: Simplified model of pottery traditions in the LBK (Claßen 2009)

Premise: Women making pottery.

Idea of change in pottery style happening due to:

- exogamy (changing place of residence): women from one pottery tradition comes to a region with a different tradition

- learning: the newcomer adopts the local main motif of decoration learned from local women

- change: happens in form of adding secondary motifs of decoration that the newcomer brings from her home community

Implications of the model

- Change happens only at a certain moment of time: when the newcomer comes into the community and is combining the local and foreign motifs

- No space for individual invention and agency.

Model

Premise: Men making polished stone tools.

If we apply the same model on the polished and beveled stone tools:

Men are mostly local (e.g. Bentley 2012)

→ no foreign input → no change in case of polished tools?

Therefore…

- There are not large changes in shape variation of axes and adzes.

- There is a shared idea of both the:

- shared manufacturing practice and

- ideal shape the final artefact will take.

Both of these are learned…

The variation originates from small decisions taken during the process of manufacture.

Conclusion

The decisions leading to variability in shape and size of polished and beveled stone tools are initially small and insignificant caused by personal preference, skill, technological necessity or a combination of these and cumulatively result in a larger and significant outcome (inspired by the tyranny of small decisions).

References

Bentley, R. A., Bickle, P., Fibiger, L. et al. 2012. Community differentiantion and kinship among Europe’s first farmers PNAS 109, 9326-9330.

Claßen, E. 2009: Settlement history, land use and social networks of early Neolithic communities in western Germany. In Creating Communities: New Advances in Central European Neolithic Research, eds. D. Hofmann, P. Bickle, 95-110. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Hampton, O. W. Bud 1999: Culture of Stone. Sacred and Profane Uses of Stone among the Dani. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Pétrequin, P., Pétrequin A. M. et al. 1998. From the Raw Material to the Neolithic Stone Axe. Production Processes and Social Context. In Understanding the Neolithic of North-Western Europe, eds. M. Edmonds, C. Richards, 277-311. Glasgow: Cruithne Press.

Pétrequin, P., Pétrequin, A. M. 2011: The twentieth-century polished stone axeheads of New Guinea: why study them? In Stone Axe Studies III, eds. V. Davis, M. Edmonds, 333-349. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

Prostředník, J., Šída, P., Šrein, V., et al. 2005: Neolithic quarrying in the foothills of the Jizera Mountains and the dating thereof. Archeologické rozhledy LVII, 477 – 492.

Toth, N., Clark, D., Ligabue, G. 1992: The Last Stone Ax Makers. Scientific American 267/1, 88-93.